Moral and Technological Progress 2

It’s difficult to question the progress of technology and science. However, during the aptly named Progressive Era, the inexorable march of sci/tech became confused with the inexorable march of moral progress. The two shapes of time—moral and technological progress—became interlinked. Looking back at this interlinkage, i find much to admire in its resultant philosophy. I don’t agree with it entirely, of course, but it’s better than the progressivism of today. A Cathedral cleric writes about it disapprovingly:

It is a Whiggish temptation to regard progressive thought of a century ago as akin to contemporary progressivism. But, befitting the protean nature of the American reform tradition, the original progressives entertained views that today’s progressives, if they knew of them, would reject as decidedly unprogressive. In particular, the progressives of a century ago viewed the industrial poor and other economically marginal groups with great ambivalence. Progressive Era economic reform saw the poor as victims in need of uplift but also as threats requiring social control, a fundamental tension that manifested itself most conspicuously in the appeal to inferior heredity as a scientific basis for distinguishing the poor worthy of uplift from the poor who should be regarded as threats to economic health and well-being.

So, while progressives did advocate for labor, they also depicted many groups of workers as undeserving of uplift, indeed as the cause rather than the consequence of low wages. While progressives did advocate for women’s rights, they also promoted a vision of economic and family life that would remove women from the labor force, the better to meet women’s obligations to be “mothers of the race,” and to defer to the “family wage”. While progressives did oppose biological defenses of laissez-faire, many also advocated eugenics, the social control of human heredity (Leonard 2005b). While progressives did advocate for peace, some founded their opposition to war on its putatively dysgenic effects, and others championed American military expansion into Cuba and the Philippines, and the country’s entry into the First World War. And, while progressives did seek to check corporate power, many also admired the scientifically planned corporation of Frederick Winslow Taylor, even regarding it as an organizational exemplar for their program of reform. Viewed from today, it is the original progressives’ embrace of human hierarchy that seems most objectionable. American Progressive Era eugenics was predicated upon human hierarchy, and the Progressive Era reformers drawn to eugenics believed that some human groups were inferior to others, and that evolutionary science explained and justified their theories of human hierarchy.

It sounds to me like the progressivism of the Progressive Era had yet to become one-eyed. Scientific and moral progress were coupled together, which meant that, for a brief moment in American history, one ideal kept the other’s excesses in check. This explains people like Margaret Sanger, who believed in the moral progress of racial equality but also realized that, empirically, the best way to achieve racial equality was through serious eugenic policies for blacks.

Today, in practice and in reality, moral and scientific progress are completely de-coupled. This explains people like [insert random progressive here], who believe in the moral progress of racial equality but have no empirical foundation for bringing it about, and so resort to a magical defensive tactic (“institutional racism!”) to explain why the good magic hasn’t happened yet. Today’s progressives are often outright hostile to notions of scientific progress.

Nevertheless, despite the reality, in today’s progressive and popular imaginations, moral and technological progress still are one and the same, inextricably linked. This is an epiphany I had while teaching class today. I overheard some students talking, and they seemed to reject a right-wing position as quickly and thoughtlessly as though they were rejecting the use of horse-and-buggy as a means of transportation to tonight’s sorority party. “Oh, people just don’t think that way anymore” or “We’ve moved beyond that kind of philistine thought” or “That is so how my grandfather talks!” As though notions of sovereign borders were as quaint as Ptolemaic cosmology.

Moral and technological progress are two non-overlapping time-shapes. The latter is empirically observable, the former is either a fiction or a temporary reprieve from Hobbesian violence safeguarded by high-trust civilizations. In the American Progressive Era, they were coupled together, with interesting and not entirely unsatisfactory results. Today, we operate only with the Progressive Era’s belief in moral progress, but this belief is, among the progressive elite, de-coupled from a concomitant belief in scientific and technological progress. No more checks and balances. The one-eyed, headlong pursuit of the Moral Prize hurtles us toward Left Singularity.

Two Shapes of Time: Moral vs. Technological Progress

Nick Land’s unfolding series The Shape of Time—well worth the read, like all of Land’s multi-part essays—quotes John Michael Greer at length in an attempt to summarize the various ‘time shapes’ with which the Occident has ordered time and understood its place in the unfolding expanse of it. Land, following Greer, identifies two major shapes: the Augistinian and the Joachim.

The former is the Christian time shape, beginning with Creation and the Fall, ending with The Last Day and Paradise. Everything in between—that is, secular history—is merely the muddled middle through which God and Christ lead the elect.

The Joachim time shape, on the other hand, is equted with the contemporary progressive ordering of time. Greer describes it:

To Joachim, sacred history was not limited to a paradise before time, a paradise after it, and the thread of the righteous remnant and the redeeming doctrine linking the two. He saw sacred history unfolding all around him in the events of his own time. His vision divided all of history into three great ages, governed by the three persons of the Christian trinity: the Age of Law governed by the Father, which ran from the Fall to the crucifixion of Jesus; the Age of Love governed by the Son, which ran from the crucifixion to the year 1260; and the Age of Liberty governed by the Holy Spirit, which would run from 1260 to the end of the world.

What made Joachim’s vision different from any of the visionary histories that came before it — and there were plenty of those in the Middle Ages — was that it was a story of progress.

Yes, a story of progress, but almost certainly a story of moral progress.

~~~

The progressive time-shape—an ordering of time which denies the existence of feedback loops, regression, cycles, a complexly but systematically enforced sustainability—has today developed conceptually along two disconnected axes: the moral and the technological.

The first is exemplified by radical, millennial Protestantism and its belief in the perfectability of mankind. The ordering of time along an axis of ever-perfecting moral progress was the explicit assumption of John Noyes and other 19th century North American utopian Christians; it is the implicit assumption of the progressive Left in the 20th and 21st centuries. It is given its clearest form in Martin Luther King Jr.’s gnomic apothegm: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” The axis of time stretches in one direction; its purpose is predominantly moral; and its terminal point is the moral perfection of human beings. The discourse of the progressive Left constantly reaffirms this sense of universal purpose.

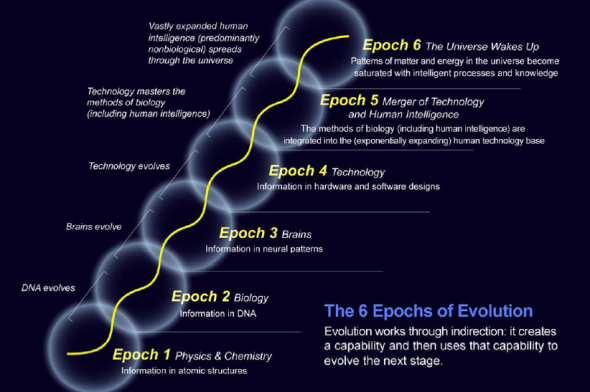

However, the ordering of time along an axis of ever-expanding technological progress has little to do with the time shape of moral progress. Ray Kurzweil is the obvious exemplar in this case. The first chapter of The Singularity is Near explicitly orders the history of time according to Six Epochs, each representing a more advanced stage of knowledge and/or technological progress than the epoch that came before it: Epoch One: Physics and Chemistry. Epoch Two: Biology and DNA. Epoch Three: Brains. Epoch Four: Technology. Epoch Five: The Merger of Human Technology with Human Intelligence. Epoch Six: The Universe Wakes Up.

This time shape is given its clearst form in the idea that “humans are the minds through which the universe comes to know and marvel at itself.” Humans with the highest IQs and most advanced technology are obviously in the best position to further travel along this arc of technological progress toward singularity.

~~~

Those who order time according to the shape of Moral Progress rarely have any affinity for those who order time according to the shape of Technological Progress. And vice versa. They see time expanding toward very different (though, I suppose, not mutually exclusive) goals.

My personal preference is obviously for the latter time shape: technological progress. I am only concerned with moral progress insofar as vice leads to social disorder and instability, which are not optimal for the progress of knowledge and technology. I have, for most of my adult life, been a firm believer in technological progress; even in my nominally Leftist days, however, I was skeptical about the existence of moral progress. As a neoreactionary, I outright deny it.

In general, good evidence exists for accepting the one time arc but denying the other. Moral progress is a blatant absurdity. Slavery is as rampant today as it was a thousand years ago; wars and rumors of war never cease. The idea that the species can be improved in some way, as Cormac McCarthy said, is a false idol, and those who worship it make their lives vacuous and corrupt. My rejection of progressivism is ultimately a rejection of the belief in moral progress; it also results from the belief that those who try to push the world along a time arc that doesn’t actually exist are usually the ones pushing it, at various times and places, into the social disorder and instability they seek to obviate.

Conversely, technological progress is a blatant reality. Isn’t it? Science would look like magic to human populations from just a few hundred years ago. Diseases have been eradicated or made easily treateable. A thouand years back, humans hadn’t made it across the Atlantic Ocean; now we fly over it in a few hours; hell, making it to the moon isn’t too much trouble . . .

That is to say, making it to the moon wasn’t too much trouble at one point. Today, NASA can’t even put a person in low-earth orbit.

Technological progress has clearly occurred, but its continuation is not inevitable. In hindsight, this should be an obvious point. The success of 20th century science has led me to be more optimistic than history warrants. And I’m not even talking about the collapse of Rome. That regression was relatively minor compared to regressions on longer time scales in deep history. At some point, a population of archaic hominids found themselves stranded on the island of Flores in Indonesia. Over the course of the next ten thousand years, their brains shrunk. And then shrunk some more. They continued to use basic tools, but they were destined never to advance like their distant cousins who stayed in Africa and Europe. As Razib Khan puts it here: “I can believe that a local adaptation toward small brains, Idiocracy-writ large, occurred. Brains are metabolically expensive, and it isn’t as if the history of life on earth has shown the massive long-term benefits of being highly encephalized.”

Regression. To a Westerner in 2013, the notion of regression is frightening, nearly horrific. In most dystopian visions, things regress, but somewhere someone retains high-tech knowledge and skill. Earth in Elysium may be one giant Mexican city, but the whites, Indians, and Asians on Elysium itself have advanced closer toward Singularity. In Wells’ vision, the Eloi are docile illiterates, but the Morlock still know how to run the machines.

A global regression, on the other hand, means that everyone has forgotten. Lost knowledge of the ancients. My modern bias tells me that the ancients didn’t know anything worth knowing in our age of science, but maybe that’s not true. Regardless, if contemporary knowledge is lost, then our distant idiot ancestors will have lost the knowledge of the ancients.

If we take Greer’s and Land’s thesis seriously—that any time shape positing an Arc of Progress is seriously problematic—then we must prepare ourselves for the possibility that a technolgoical Elysium is as unattainable, or, at least, as unlikely a goal as a moral Utopia. That’s a hard pill to swallow for a futurist. One can only hope that the complex cycles of time always come around to this same place again. If Science, Technology, and Reason are transient, humanity can always look forward to their return.

The World Is That From Which There Is No Escape

Among many other things, Nick Land’s “Lure of the Void” series is a poetic, though only partially metaphoric exploration of Exit and the forces that keep it closed. In the series, space is figured as the unending frontier into which people could literally free themselves from terrestrial controls and concerns, that is, the concerns of the neopuritan Left (how can you bring Heaven to earth when you’ve already left for the heavens?). The Cathedral has thus de-emphasized the political theatrics of the Space Age, made space exploration a part of history, not a part of the future. Land writes:

Disillusionment is simply awakening from childish things, the druids tell us. This is a point Murphy is keen to endorse: “space fantasies can prevent us from tackling mundane problems.” Intriguingly, his initial step towards acceptance involves a rectification of false memory, through a (sane) analog of ‘Moon Hoax’ denial. Surveying his students on their understanding of recent space history (“since 1980 or so”), he discovered that no less than 52% thought humans had departed the earth as far as the moon in that time (385,000 km distant). Only 11% correctly understood that no manned expedition had escaped Low Earth Orbit (LEO) since the end of the Apollo program (600 km out). Recent human space activity, at least in the way it was imagined, had not taken place. It was predominantly a collective hallucination.

Murphy’s highly-developed style of numerate druidism represents the null hypothesis in the space settlement debate: perhaps we’re not out there because there’s no convincing reason to expect anything else. Extraterrestrial space isn’t a frontier, even a tough one, but rather an implacably hostile desolation that promises nothing except grief and waste. There’s some scientific data to be gleaned, and also (although Murphy doesn’t emphasize this) opportunities for political theatrics. Other than that, however, there’s nothing beyond LEO worth reaching for.

~~~

This week, NASA put what may be the first nail in the coffin of long-term manned space flight funded by non-private sources. The headline reads: Trip to Mars would likely exceed radiation limits for astronauts. But the limit is, naturally, a Cathedral-enforced one:

NASA limits astronauts’ increased cancer risk to 3 percent, which translates to a cumulative radiation dose of between about 800 millisieverts and 1,200 millisieverts, depending on a person’s age, gender and other factors.

“Even for the shortest of (Mars) missions, we are perilously close to the radiation career and health limits that we’ve established for our astronauts,” NASA’s chief medical officer Richard Williams told a National Academy of Sciences’ medical committee on Thursday.

I don’t doubt for a second that most astronauts would gladly sign on for long-term space flights even if such adventures increased risk of cancer in later life. Nor do I doubt that these astronauts will gladly work for yet-to-be-founded private companies that, like governments of yesteryear, refuse to give up advancing knowledge and profit simply because the pursuit might be a little dangerous. But this latest NASA announcement proves the general validity of Land’s thesis: the Cathedral, quite literally, does not want the humans to escape.

~~~

ADDED: Land points me to aerospace engineer Rand Simberg, who writes:

The history of exploration of new lands, science and technologies has always entailed risk to the health and lives of the explorers. Similarly, the history of settlement of new territory is a bloody one, with great risk to the settlers. Had they not taken those risks, we might still be in the trees in Africa, and unable to write books like this on computers. Yet, when it comes to exploring and developing the high frontier of space, the harshest frontier ever, the highest value is apparently not the accomplishment of those goals, but of minimizing, if not eliminating, the possibility of injury or death of the humans carrying them out.

Anti-science Fiction

If you enjoy reading too much into things (and I do), you can read Jurassic Park as Luddite, anti-science propaganda. The ethical impulse of the entire film rests on Ian Malcolm’s famous line: “You were so concerned with whether or not you could, you never stopped to think if you should.” The movie plays out as a prolonged justification of Malcolm’s ethical wisdom, culminating in several scenes in which the paleontologist heroes essentially decide, nah, screw this research opportunity, it’s too dangerous, let’s go back to digging for bones in the dirt. Much better to be ethical than to extend the bounds of knowledge.

The film is a cautionary tale about scientific hubris, but that gets me thinking about the “scientific hubris” trope more generally. Beginning with Shelley’s Frankenstein, there is a strand in Western film and literature dealing with science or technology, even straight science fiction, that can be described as one giant cautionary tale against scientific hubris. In the past, this anti-science strand was always counteracted by the celebrants of technological progress: Jules Verne comes immediately to mind, he the great anecdote to the pessimist H.G. Wells. (Verne hated being compared to Wells.) Today, however, you’ll be hard pressed to find a Jules Verne, especially in Hollywood. From the reboot of The Manchurian Candidate to the Bourne franchise, the bad guys are more and more often rogue scientists (geneticists, usually, the worst kind of rogue scientist) and the good guys are the victims of Science, always ready with moralistic lines about Humanity.

“I’m not a science experiment, doc.”

“You were so concerned with whether or not you could, you never stopped to think if you should.”

I’m glad no one had that attitude in previous centuries. We’d still be bleeding patients and traveling by stagecoach.

There aren’t many films or novels these days whose protagonists are headstrong researchers pursuing knowledge and advancement at any costs, even though the achievements of Western civilization rely on headstrong researchers pursuing knowledge and advancement at any costs.* When did you last see a film or read a book in which the bad guys warned against scientific hubris, in which the antagonist was the guy who tries to thwart the geneticist from conducting a human experiment?

Not in America. For that, you need to go to Japan:

If you haven’t seen it or read it, I highly recommend Paprika. The story follows two psychiatrists who have invented devices that allow people to watch, record, and even enter one another’s dreams. The antagonist is Dr. Inui, a wheelchair-bound purist who believes the devices are unethical and dangerous, and who will go to great lengths—even murder—to stop the devices from being used. Inui considers himself the “protector of human dreams” from the audacity of science. The book describes him as “obsessed with justice” to a “dangerous” degree. He delivers puritanical speeches against the pro-research protagonists:

You see yourselves as brave pioneers riding on the leading edge of discovery! Where’s your sense of social responsibility? You should be ashamed to call yourselves scientists!

He critiques the Western notion of scientific genius from a Marxist perspective:

You seem to think you developed the devices all by yourself, but that’s merely the product of vanity. You didn’t. What about the investors who provided all the funds, the engineers who installed the equipment, the assistants, even the cleaning ladies? You can’t claim the invention as your own.

In other words, Inui is the Cathderal. And he’s the bad guy. Don’t expect authors outside the Sinosphere to start putting words like the ones above into the mouths of anyone but their holier-than-thou, anti-scientific heroes.

*TV medical dramas are the exception to this new rule. House and Doc Martin are especially enjoyable; both characters care far more about science and medicine than they do about bedside manners or ethics committees.

Recent Comments